fake disorder cringe?

why does a subreddit dedicated to finding disorder fakers have 290k members?

I have TMJ disorder, which stands for temporomandibular joint disorder. For me, it means my jaw carries too much stress until it spills out into other parts of my body—my temples, my head, my neck, my inner ears. This causes a spectrum of pain and detriment to my life. On a good day, I don’t notice anything, and feel no pain. On a mild day, I feel tightness somewhere around my head, but it’s an ignorable level. On a moderate day, I’m dizzy with neck pain, light sensitivity, scent sensitivity, and just one too-quick head turn away from nausea. On a bad day, I cannot walk or move without a debilitating headache, which I am forced to remedy with Advil.

I’ve been through thousands of dollars of misplaced treatment for my TMJ. I’ve had an 11-part round of aligners to correct my jaw, which still didn’t help. I had a bumper attached to my retainer by my dentist, which only helped temporarily. I went to one TMJ doctor who told me he could make me two splints for $3000, out of pocket. My insurance does not consider TMJ a medically necessary disorder to be treated.

The second TMJ doctor’s office I went to had a cute waiting room, with a board showing customizable letters: WELCOME SUMMER! I asked if it was for me, and the receptionist said yes. I settled in, surprised; the other doctor’s office was cold and devoid of life. This doctor had ubiquitous positive reviews online, and I could see why.

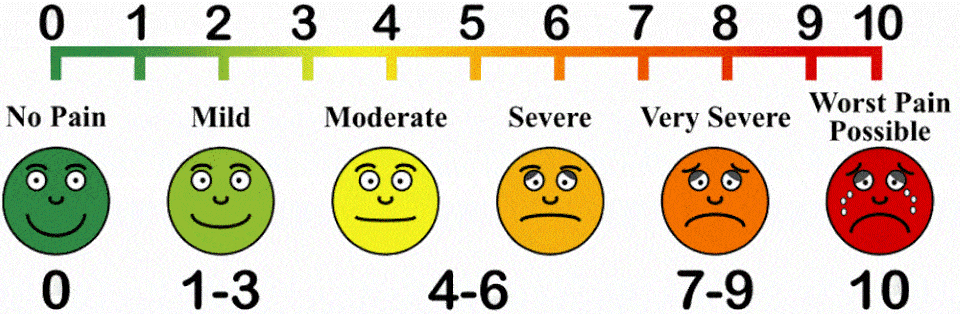

Once I got in the office, I explained my symptoms, my past failed treatments, my concerns. The doctor asked me how I’d rate the worst of my pain, from 1-10. I said 7. He immediately let out a small laugh, then said, “A 7 would be equivalent to labor pain. Are you sure?”

I looked at the little poster on the wall, showing cartoon faces experiencing each numeric scale of pain. 7 was very severe. I guess what I had was not very severe. He had to know best—he was the doctor.

“Oh,” I said. “I guess a 5 then.”

The doctor had the reaction of a math teacher who heard their student say the wrong answer to a problem, then give the correct one after some prompting. Taking less offense to my second answer, he pressed on with questions. I felt that familiar twinge in my gut telling me I betrayed myself.

He moved onto testing the sites of my pain—I was to rate each site from 1-3, with 3 being the most painful. These tests involve pushing onto affected muscle areas to discern sites of tension. He went between 15 places on my jaw, in my mouth, in my head, in my neck, and in my shoulder. My answers rarely dipped below a 3. He pressed so forcefully in my mouth that my eyes begun to water and my body wished to flee the room. On a particular squeeze between my shoulder and neck, I audibly winced, and the doctor chuckled. “That one hurt, right?”

Yes, fucking obviously. I felt myself mentally shutting down. He wasn’t here to help me and never was. The first doctor only tested 5 sites of pain, and much more gently, still producing results. It didn’t have to be this way. I was confused. I was in more pain than I was walking into this doctor’s office, and all he did about it was laugh like I had made some small talk joke.

I left the office, passing the WELCOME SUMMER! sign, went home, and cried. I considered writing an honest, negative review on his Yelp, but was unnerved by the fact that no one had a similar dismissive experience like me. I looked up the pain scale again, trying to see if there was some unknown guide I was supposed to abide by. Not being able to function without Advil is a 7, right? Crying from the amount of pain you’re in, when you tend to stay silent until your pain is extreme, must qualify as severe?

***

Lately, I’ve had recurring suspicions that I am on the autism spectrum, at least on a subclinical level. At the very least, autism explains my thought processes, behaviors, and sensory issues I’ve had my whole life. It gave me a potential answer, reassuring me that it is not that I fail at adapting to the world; it is that the world is not made for me.

I emphasize the possibility that I have autism for several reasons, the main one being that I am not professionally diagnosed nor do I have $2000 to spend on obtaining a diagnosis. There is still a decent enough chance that I do not have autism, and that I happen to have lots of overlap with autism symptoms. But there is also a voice in my head asking me if I am faking it, if I am lying.

What if I was faking, though?

Perhaps the more interesting question my brain settles on: so what if I’m faking? What would that matter? How would I react to myself? How would others react to me?

How do I imagine others react to me?

How do I punish myself with my idea of how others will react to me?

***

Autism goes underdiagnosed in nonwhite communities, in low-income communities, and in marginalized genders. Our concept of autism is built around middle-to-upper-class white boys, and thus diagnostic criteria and access skew towards that demographic as well. As a result, many girls grow up unaware that they have autism, and they only find out after self-diagnosing with online resources, or testing as adults. For many, life is just difficult for a reason they cannot pinpoint. Self-diagnosis can provide tools, advice, and community support for individuals who cannot access diagnosis.

There is a mindset of scarcity when it comes to self diagnosis. There is a belief that, by self diagnosing, you are taking away some quantifiable value from those who are professionally diagnosed. I struggle to find actual proof of this. Those who subscribe to this scarcity and anti-self diagnosis mindset will point out people online who crowdfund for an illness they “don’t have,” according to other online users. More often, these “illness fakers” will be labeled attention seekers and cringe fodder, whose existence mocks people who “actually have” the illness.

At least, this is the overall sentiment expressed in the subreddit r/fakedisordercringe. I stumbled upon this forum through r/evilautism, where people express their hatred for this subreddit. In this r/fakedisordercringe, users will find examples of what they believe are mental disorder fakers, then reupload their content for everyone to make fun of. It is common to see teenagers from 13-18 be the subject of these posts. They pick apart every detail of a bio or post or video; many of these disorder lists happen to include Autism and ADHD. (Many of these subjects of ridicule are also LGBT and genderqueer, whose youth often experience familial abuse and peer isolation.)

This subreddit disgusts and fascinates me in equal measure, as I feel that they have stumbled upon a deep insecurity that they aren’t aware of. I hypothesize that they’re insecure that they could be the illness faker they hate so much, and the only thing denoting their moral status is a professional diagnosis, or some other external validation outside of their control. They did it the right way. They are sure they have their condition. They did the work to validate their illness, unlike others who can just read words online and add a disability into their bio. The real illness-havers saw a gate and were allowed through, and letting just anyone through would mean the work they did was pointless.

These anti “illness-fakers” try to police who has a real illness and who does not, because the alternative is to accept the idea that disability is not a universal, consistently quantifiable, binaried state. The alternative is to believe that you do not require a diagnosis to be kinder to ourselves, more forgiving, and more accommodating, regardless of what we are formally diagnosed with or not. The alternative is to believe that neurotypicality does not assign any winner, and there is no prize to be had in delineating who is a secret neurotypical and who is not. There is no “good” disabled and “bad” disabled. Your suffering in obtaining a “real” diagnosis did not make you more virtuous; you actually should not have suffered at all.

This brings me back to my main question: so what if these people are faking their illness? Let’s put aside the fact that they may genuinely have these disorders. When we fake something, we are looking for attention. It is normal for a child to make up a grass allergy, or fake a vision test to get glasses; these are acts that ask for peer and adult attention. These acts unequivocally demand care and community, especially at a time in life where a child has no agency. They ask for one to be recognized as special, when internal feelings of self-worth are unstable. It names a concrete quality that others can understand easily and give attention to.

If you have ever faked an illness to get out of school or work, why is that the reason you chose? Why did it work? And did you feel any guilt about it? Did it feel morally wrong? I would guess the answer is no to the last two questions. I would guess that you had a legitimate reason to not go into work—it could be so simple as “you didn’t feel like it.” It could be as simple as the fact that our time should belong to us, and we will use any reason necessary to get our time back. Pain is a universal language, so it warrants an incontestable form of attention and sympathy.

There is more danger in assuming one is faking an illness than there is in believing an “illness faker.” The consequences can be literally fatal; it is an unfortunate fact that some doctors do not take patients seriously, and routinely commit neglect, malpractice, and misdiagnoses that lead to harm and death. The quantifiable illness-faker sentiment lies in doctors. It is in the excessively forceful squeeze into my shoulder, the revision demand of my pain level. It is in the way you have to do extensive research online for a good doctor, for fear of your concerns being ignored or your treatment being misplaced. It is in the way we have to actively protect ourselves against professionals who don’t believe us under the medical industrial complex.

This cultural animosity towards the elusive and rare “illness faker” is embedded in our ableist society. It is what happens when our society assumes everyone to be abled unless there is physical, “undeniable” proof. This, in turn, invalidates invisible disabilities and disorders that do not outwardly prevent function at all times. At the same time, we ignore the illnesses and conditions we may have because they do not seem overt or “bad” enough. Our white supremacist, classist notions of western illness also harm any nonwhite, non-cis, queer, marginalized body by refusing to acknowledge the way illness shows up for us. In fact, our ableist society criminalizes marginalized people with mental illnesses, especially young black boys.

Meanwhile, the scarcity mindset towards illness fakers is a product of our ableist American society that does not provide universal healthcare, this creating limited resources for the injured and disabled. One could argue that an illness faker could crowdfund money that may have gone to a “real” disabled person insteaad—that this act steals money from the disabled. However, crowdfunding would not have to exist if our healthcare needs were met by the government, or if we had enough money to live happy lives. It is the for-profit healthcare system that robs us, with its inflated medical bills and subpar care. Crowdfunding is a last resort that people turn to when everything else has failed them.

After my experiences at the doctor and on online forums, I realized this: I know my body best. I am the one living in my body. If I believe something, it is because I have reason to. If I am faking all along, I had reason to, that still warrants concern. No one can experience my body and my life but me, and I am the only one who can advocate for my health. My decisions do not exist in a vacuum, and disability does not exist in a vacuum. I will live and die in this body, and I owe it to myself to do what I can to make my life more comfortable.

Because if I don’t believe myself, who will?

***

from The Bad Patient, which inspired my essay:

“Even outside forums for obsessives, most of us want to believe there’s a bright line between the really sick and the fake sick, between the sincere expression of suffering and the over-the-top, between the patient in need and the attention seeker. But I am not so sure that such a line exists. I am “really sick” — not that I intend to provide a doctor’s note; you’ll just have to trust me — and the sicker I have become, the more one thing has become clear to me: every sick person is, in some way, an illness faker.”

in sum: there’s this public outcry against supposed neurotypicals/abled wolves in neurodivergent/disabled clothing. when if anything, it’s often nd/disabled in nt/abled clothing...